Dr. Miles’ Restorative Nervine

We’re back after a long - long - hiatus! Stay tuned for more articles in the coming months!

As many of you readers may know, Ruthmere and the family who lived in it – the Beardsleys – have a relationship with Miles Laboratories that spans about 140 years. Albert R. Beardsley did not yet live at Ruthmere (or have the abundant funds to build it) when Dr. Miles approached him with a new business venture in 1889, but he was already making a name for himself in Elkhart. Albert had a keen eye for marketing, which was precisely what Miles needed in order to gain footing in the pharmaceutical industry.

The Miles Medical Company in 1892. Pictured from left to right is: Emil T. Stronquist, stenographer; William B. Cranis, chief stenographer; Edwin P. Kellogg, chief bookkeeper; Mrs. Edna Billington Simpson, stenographer; Mrs. Bessie Smith Burris Boylen, stenographer; William C. Johnson, advertising manager; Albert R. Beardsley, chief executive and treasurer; Mrs. Florence Throop Gordon, stenographer and clerk; Mrs. Millie Myers Havourd, stenographer and clerk; E. C. Swayne, clerk; and William Gardner, office boy.

I’ve been thinking quite a lot lately about what the world of medicine was like when Dr. Miles first approached Albert Beardsley. The entire concept of a “pharmacy” was relatively new (a more regulated, standardized business than the apothecary of yore) and the professions of doctor and pharmacist often overlapped as these medical scientists explored new, innovative methods of treatment and chemical formulas. Large-scale drug manufacturing was in its infancy in the United States. In many ways, Miles was as much an entrepreneur as he was a doctor, perhaps out of necessity – he had a product he knew worked, and he needed to find a way to get it out into the world. I often wonder: did Albert see this endeavor as a risk?

Did Albert, or perhaps his wife, Elizabeth, try Dr. Miles’ medicine before agreeing to take part?

Miles’ primary product at the time was DR. MILES’ RESTORATIVE NERVINE, a groundbreaking tonic that ultimately paved the way for several other medicines of its type. Working at Ruthmere, I’ve seen this label countless times and noted, with piqued curiosity, that Nervine was not a product that Bayer continued to produce after absorbing Miles, unlike Alka-Seltzer and One-a-Day Vitamins. Though you’ll find medicine with similar, weakened effects on the shelves, the product itself is defunct, and anything as strong as Nervine would need to be prescribed by a doctor. Why, you may ask? What exactly was Dr. Miles’ medical cure-all, Nervine, and why can’t I run to CVS and buy some today?

In The Dr. Miles Medical Company’s own words, Nervine was a tonic made to cure…

“Apoplexy, Backache, Bilious Attacks, Blues, Chills, Chorea, Cold Hands and Feet, Convulsions, Coughs, Colds, Cramps, Delirium Tremens, Dizziness, Drunkenness, Dullness, Dyspepsia, Epilepsy, Fits, Exhaustion, Fluttering of the Heart, Giddiness, Hay Fever, Headache (Sick, Nervous, Bilious), Heaviness, Hot Flashes, Hysteria, Influenza, Insanity, Irritability, Mania, Melancholy, Monthly Pains, Morphine Habit, Nervousness, Nervous Dyspepsia (Prostration, Exhaustion), Neuralgia, Numbness, Opium Habit, Pain, Palpitation, Poor Memory, Pressure in Head, Profuse Menses, Rheumatism, Sea Sickness, Sexual Debility, Sleeplessness, Spasms, Spinal Irritation, Vertigo, Vomiting.”

Please note that Miles chose to use the word “cure” and not “help with.”

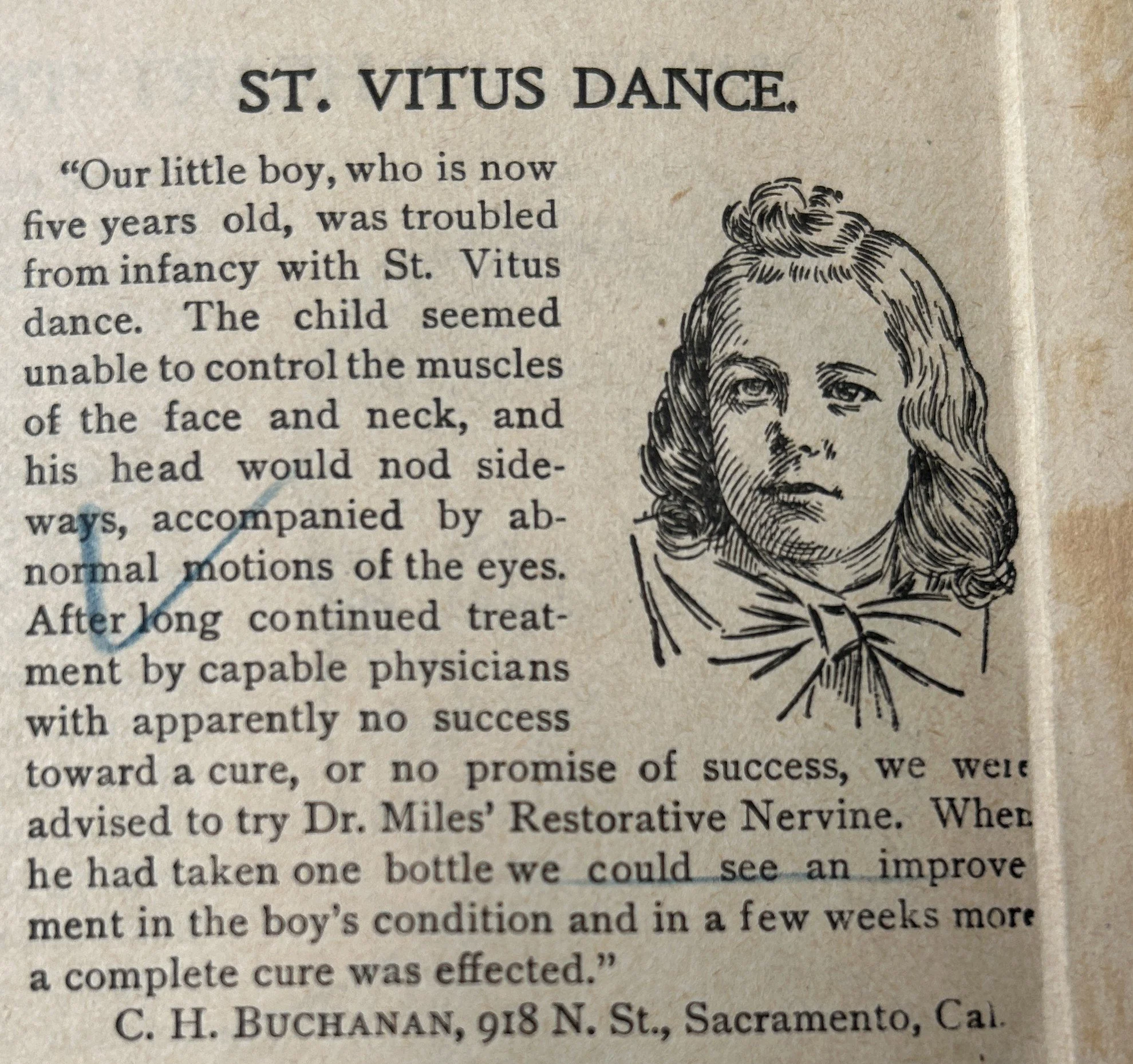

Indeed, Miles’ Nervine was marketed as a cure-all miracle drug. This long, long list comes from an 1890s publication called “The Doctor,” which would have been published not long after Albert Beardsley came onboard. Testimonials, paired with sketches of supposedly real people, give truth and humanity to the claims that Nervine can, and has, helped with these maladies. Take a look at a few.

To figure out what Nervine actually did, we’ll take a look at its three major ingredients: sodium, potassium and ammonium bromides. According to Wikipedia, sodium bromide “has been used as a hypnotic, anticonvulsant, and sedative in medicine, widely used as an anticonvulsant and a sedative in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.” Potassium and ammonium bromides have much the same effect. Some side effects I found in research are lethargy, jerky movements, loss of appetite, skin rashes, blisters, acne, agitation, memory loss, and hallucinations.

Sedation is used for a wide variety of purposes in medicine, and has been for a very long time. Notably – and this is where I get to plug my upcoming Gallery Talk later this year – it has been used to treat female “hysteria.” This was essentially a blanket term for any unusual behaviors displayed by women that made society (men) uncomfortable, but it could also include actual medical conditions such as some of the ones listed above. Hysteria is right there in that long list. To his credit, Miles did not claim in any of the publications I read that hysteria was a female-specific disorder. That might have gone without saying, but it’s still noteworthy that they chose to use the word “person” and not “woman.” Come see my Gallery Talk on September 5th to learn more about women’s healthcare in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Bromides were not the end-all be-all of cures for these issues, obviously. Barbiturates, which entered the medical scene in the next century, were considered safer drugs with similar sedative effects. Still, Miles continued to produce Nervine, even after it was vastly overshadowed by Alka-Seltzer, for many decades after its creation. I tried to find a concrete time when Miles stopped producing Nervine – easier said than done.

In 1950, Miles debuted Bactine, “The Family Antiseptic,” that many might remember being used on their cuts during childhood (and it’s still being made today by Bayer). In the May, 1950 issue of The Alkalizer (Miles’ employee newsletter), they introduced Bactine to employees, but later in the issue included a blurb that said “Don’t Forget!” about Nervine, an “old friend.”

A May 1966 issue of The Alkalizer included an article with the history of the company which stated, “Miles Nervine, as it is known today, is still going strong, and is available in capsules and effervescent tablets as well as in its original liquid form.”

Still, it was competing against controversy surrounding the use of bromides. According to Miles: A Centennial History by William C. Cray, “Nervine slowly moved to the proprietary sidelines… Late in the 1970s, the FDA removed [bromides] from the market. Miles had excised bromide from Nervine’s time-honored formula shortly before, replacing it with an antihistamine. In this way, the venerable name, in new dress, quietly remains on the market.” This book was published in 1984.

And beyond that… well, it seems to have vanished. My guess is that Bayer didn’t want to continue selling Nervine after buying the company out, so they just – to use the word of William C. Cray – quietly stopped production. If anyone knows of an exact year that they stopped making it, I’d love to know! I wasn’t able to find that information in my research. All I can say is that a powerful sedative like Miles’ Nervine is not something you can get over-the-counter for $1/bottle like you could in the 1890s.

And that’s probably a good thing.